When citizens are systematically excluded from planning, implementation, and monitoring processes, particularly in areas like public auditing, the legitimacy, transparency, and effectiveness of governance are fundamentally compromised. Yet, in practice, citizen participation in public audit remains a critically neglected domain in Nepal.

The essence of democracy lies not merely in the right to vote but in the continuous engagement of citizens in public affairs. This engagement can be both indirect (through elected representatives) and direct (through active participation in decision-making, planning, and oversight). Unfortunately, despite strong constitutional and legal provisions, direct citizen engagement in Nepal’s governance landscape-especially in audit processes weak and sporadic.

The Participation Gap in Nepal

A comprehensive survey carried out in all 13 local levels of the Kavrepalanchok district under the Local Accountability and Transparency Initiative Project implemented by Samudayik Sarathi revealed troubling statistics. Over 79% of respondents had not participated in local planning processes, 85% were absent during policy formulation, and 83% had not taken part in any form of monitoring or oversight. These figures are indicative of a broader national trend, where citizen engagement remains largely symbolic or limited to electoral participation.

Even in the national electoral process, participation is far from optimal. In the last federal elections, only 61% of eligible citizens voted. The lack of legal provisions for absentee voting continues to disenfranchise hundreds of thousands of Nepalis living abroad. Moreover, the absence of a “None of the Above” (NOTA) option discourages participation among voters dissatisfied with the available candidates, further suppressing civic engagement.

According to TheGlobalEconomy.com, Nepal ranks 38th out of 171 countries on the Civil Society Participation Index, scoring 0.851. However, this ranking masks deeper structural issues. The 2023 Open Budget Survey by the International Budget Partnership scored Nepal a mere 31 out of 100 on public participation in budget processes-placing it in the “limited” category. This underscores the need for urgent, systemic interventions to improve civic engagement in fiscal oversight.

The Value of Citizen Participation

"Leave No One Behind" (LNOB) is the core slogan of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This phrase encapsulates the overarching commitment of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to ensure citizen engagement in all segments of the development process.

Citizen participation in governance is not a luxury-it is a necessity. As defined by development theorists like Bryson (2016), participation refers to the direct involvement of people in decisions that impact their lives. In governance, it implies that stakeholders-either directly or through representatives involved in shaping policies, plans, and programmes. Participation fosters ownership, enhances accountability, and builds trust between citizens and the state.

In her seminal 1969 paper "A Ladder of Citizen Participation," Sherry R. Arnstein argued that participation must go beyond tokenism. She defined eight levels of engagement, only three of which, namely partnership, delegated power, and citizen control, constitute genuine participation. These are the levels where power is shared, citizens influence decisions, and institutional mechanisms respond to their voices.

Globally, the concept of Citizen Participatory Audit (CPA) is increasingly gaining traction. Institutions such as the United Nations and the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) have long recognized CPA as a tool for enhancing transparency, improving governance, and combating misuse of public funds.

A 2011 joint UN/INTOSAI report emphasized that engaging citizens in audits not only increases the legitimacy of audit findings but also builds trust between citizens and the state.

Strong Legal Provisions-Weak Implementation

Nepal’s Constitution robustly endorses citizen participation. The very preamble speaks of sovereignty, autonomy, and self-rule. Article 51 (c) commits the state to ensure citizen participation in development processes. Furthermore, the 16th Five-Year Plan prioritizes inclusive participation in planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation-particularly for targeted groups.

The Local Government Operation Act (2017) obliges local governments to coordinate with civil society, the private sector, and community organizations in development and service delivery. It mandates citizen participation in project selection. Similarly, the Monitoring and Evaluation Act (2023) encourages inclusion of both service providers and recipients in evaluation activities.

The Good Governance Act (2007) and accompanying regulations require stakeholder consultation and citizen ownership in project implementation. Public hearings are enshrined as formal mechanisms for citizen feedback. Despite this strong legal scaffolding, participation in practice remains fragmented, underfunded, and under-prioritized.

Citizen Participatory Audit (CPA): An Overlooked Opportunity

Auditing is typically viewed as a technical activity conducted by financial experts to examine expenditures and detect anomalies. However, the concept of Citizen Participatory Audit (CPA) offers a transformative shift. It integrates citizens-especially civil society actors-as partners in the audit process. Their involvement can enrich audits with on-the-ground insights, enhance the credibility of findings, and foster public trust in oversight mechanisms.

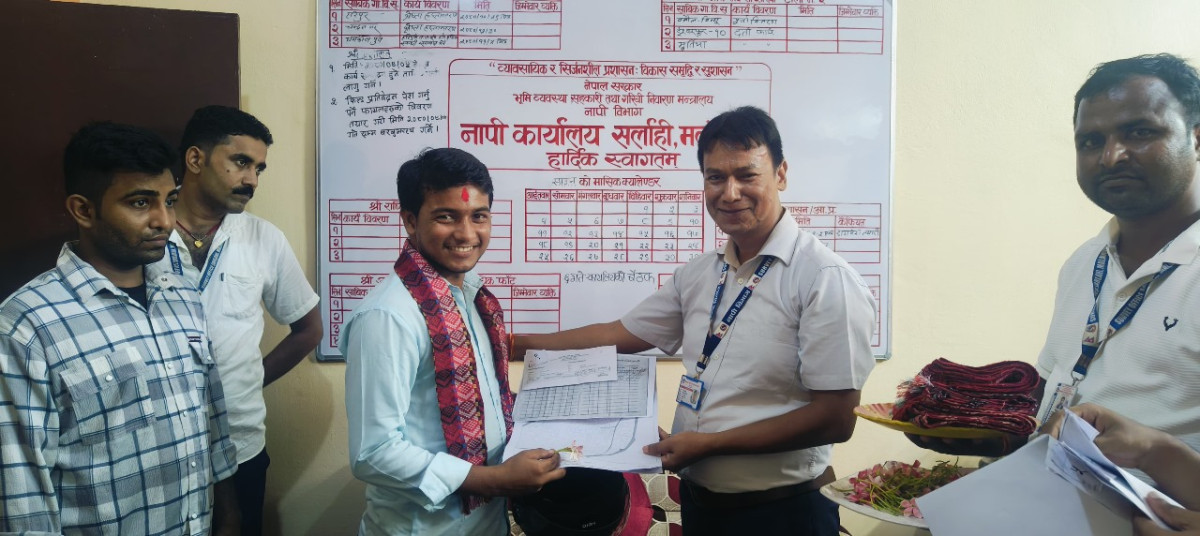

Nepal initiated CPA in 2013 (2070 B.S.) through a virtual exchange with the Commission on Audit of the Philippines, supported by the World Bank. This led to the development of a CPA Operational Directive in 2016 and its inclusion in the five-year strategy of the Office of the Auditor General (OAG). In 2017, CPA was piloted in eight earthquake-affected districts in collaboration with eight civil society organizations.

Despite these pioneering efforts, CPA has yet to be institutionalized. While the OAG conducted 15 performance audits in the last fiscal year, civil society participation in these processes remains negligible.

Challenges of CPA

Despite the promising potential of citizen engagement in auditing processes, several interlinked challenges continue to inhibit meaningful participation. A primary barrier is the perception of auditing as a highly technical field, often seen as the exclusive domain of financial experts and government officials.

This perception discourages ordinary citizens and even community-based organizations from getting involved, assuming they lack the required expertise. Compounding this is the limited public awareness about citizen participatory audit (CPA)-its purpose, scope, and entry points. Public outreach and communication regarding CPA opportunities remain minimal, and as a result, most citizens are unaware that such engagement is not only possible but also legally and institutionally encouraged.

There also exists a significant trust deficit. Many citizens are skeptical about whether their participation will have any tangible impact or lead to greater accountability. This cynicism is rooted in historical patterns of poor responsiveness from government institutions and a lack of visible consequences for corruption. Unrealistic expectations from government institutions further undermine participation. The Office of the Auditor General (OAG), for instance, often expects civil society organizations (CSOs) to volunteer their time and resources for audits without offering financial support or compensation. Such expectations are impractical and unsustainable, especially considering the time, expertise, and logistical coordination that quality participation demands.

Another major constraint is the imbalance in support structures. While international development partners have invested significantly in public sector reforms, they have largely neglected the capacity-building and mobilization needs of CSOs that are crucial for grassroots accountability.

As a result, while public institutions are strengthened, the civic actors meant to complement them remain under-resourced and underprepared. Finally, the procedural complexity of participating in audits discourages potential contributors. The current CPA framework requires civil society actors to submit proposals, undergo selection, participate in training, and enter into formal agreements-all of which demand time, resources, and institutional maturity. With no direct benefit or clear recognition, many capable organizations choose not to engage.

Way Forward

To unlock the full potential of citizen participatory auditing in Nepal, a multi-pronged strategy must be adopted-one that simplifies access, strengthens capacity, and ensures institutional ownership. First, the participation process must be simplified. The Office of the Auditor General should review and streamline existing CPA procedures, enabling concerned citizens and local organizations to raise audit issues and submit supporting documentation without being subjected to excessive bureaucracy. This would lower entry barriers and encourage broader engagement, especially from smaller, community-based organizations.

Second, technology must be leveraged to bridge the gap between central institutions and remote communities. User-friendly digital platforms can facilitate the submission of citizen reports, provide access to audit findings, and serve as two-way communication tools between auditors and the public. Such platforms would also enhance transparency and inclusiveness in real time.

Third, a nationwide awareness and communication campaign is needed to inform the public about the rights, opportunities, and mechanisms of CPA. This can be done through mass media, social media, community radio, and grassroots engagement, ensuring that citizens from all walks of life understand how they can play a role in improving governance through audits.

Fourth, it is essential to incentivize citizen engagement. Participatory auditing should be recognized as a form of professional civic service. Citizen auditors and CSOs must receive appropriate training, resources, and compensation to participate meaningfully and sustainably. Without adequate support, expectations of voluntary involvement are unrealistic and counter-productive.

Fifth, development partners must work in closer partnership with the state and civil society. Donors such as the World Bank and bilateral agencies should allocate specific funding to bolster CSO participation in oversight mechanisms. Their investments should not only target state reforms but also empower civic actors who can ensure those reforms are effectively implemented and monitored.

Finally, the Office of the Auditor General must take full ownership of this agenda. It must develop a clear and well-resourced strategy to institutionalize citizen participation as a core element of its auditing framework. This includes building strategic partnerships with civil society, organizing joint training programmes, and establishing mechanisms for continuous feedback and improvement. Through such measures, participatory auditing can become a credible, impactful, and sustainable pillar of public accountability in Nepal.

Conclusion

Citizen Participatory Audit is not just a good governance tool-it is a democratic imperative. In a context where fiscal accountability is vital to curbing corruption and ensuring service delivery, engaging citizens in public audit is both necessary and strategic.

It is time for Nepal’s public institutions, civil society, and international development partners to move from token participation to meaningful collaboration. The policy framework exists. The civic energy exists. What is needed now are leadership, investment, and institutional commitment to scale up citizen participation in audit and build a more accountable, transparent, and inclusive state.

(The author is the Executive Director, Samudayik Sarathi)

.gif)

.jpeg)

.gif)